In a sector that is powered by women and led, increasingly, by female leaders, in 2024 the gender pay gap is alive and well in the publishing sector.

To be fair to the industry, which is worth $132.4 billion globally, it has always scored well in terms of simple numbers of women working within the industry, so why does it still skew so badly towards men being given higher reward for the same roles?

However, we now see more women in management and senior positions ( 56%). So the question remains: why does this gender pay gap persist in an industry that is largely white ( 82%), mostly young, cis-women?

Part of the answer is how the industry advertises job vacancies. As an academic at the Oxford International Centre for Publishing, I spend a lot of time gathering and looking at data that might be innocuous enough on its own, but when looked at as a whole, begins to tell a stories about the industry. And, while much of my research is in digital communities, marketing, and AI, the topic of gender is never far away.

What started as a session to teach PhD candidates about data scraping and mining became a weekly hobby for me. This hobby lasted 10 months from July 2024 to April 2024. Each week I scraped the new jobs listed on The Bookseller’s job board and processed both the job title and description with a python script with a list of gender-coded root words (‘logic-’, ‘active-’, ‘assert-‘, etc. being masculine coded and ‘collab-‘, ‘cooperat-‘, and ‘interpersonal-‘, etc. being feminine coded) and from a study on gendered wording in advertising.

Over that period I scraped and analysed a total of 728 jobs across all levels and publishers in the UK. Of those jobs, every single job title was neutral in gender, which felt like a good start.

This meant that titles such as: Head of Sales, Project Executive, or Team Policy Manager, didn’t contain any of the gendered root words.

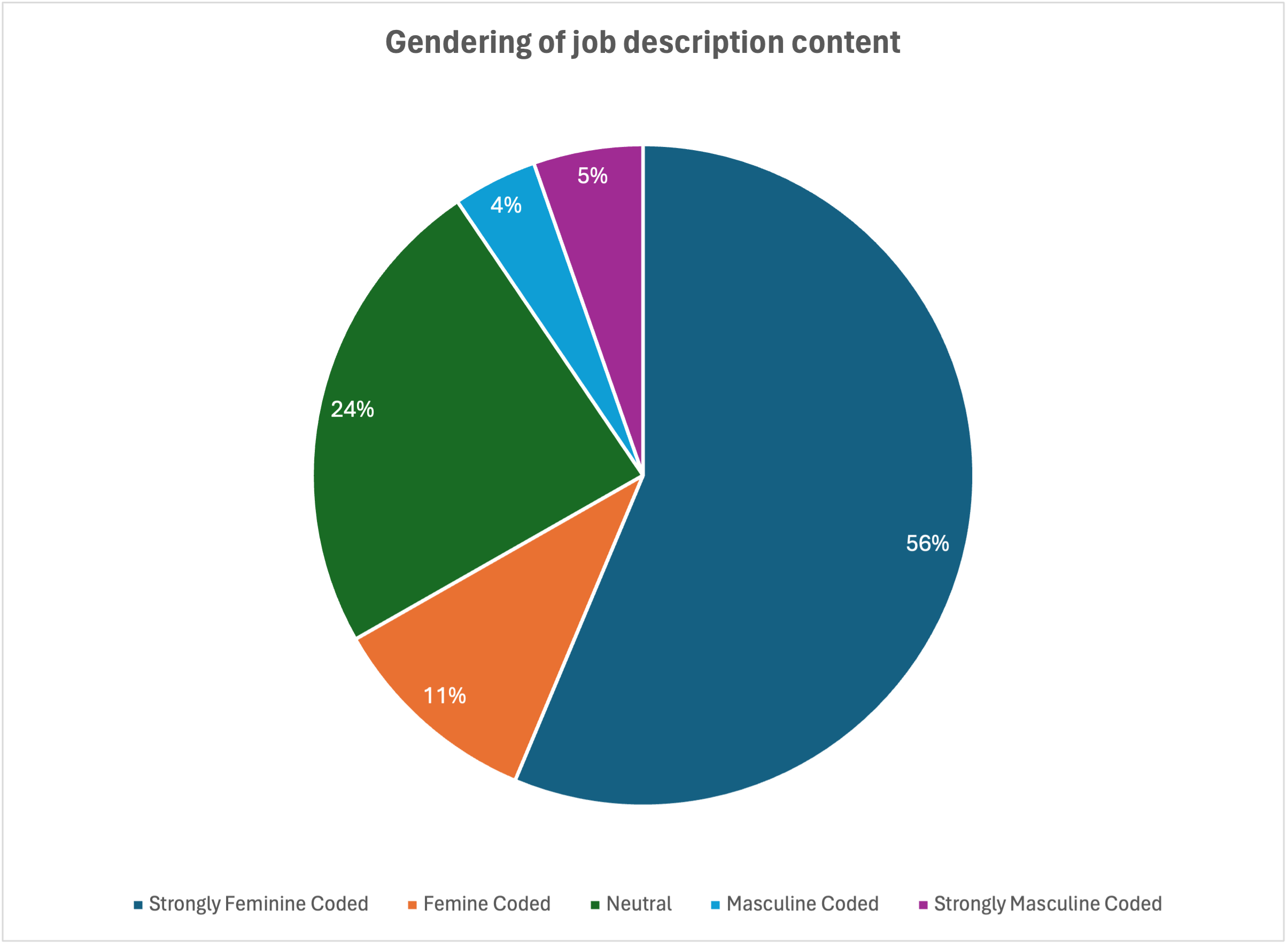

But when we dig into the details of the job descriptions themselves, we find that of the 728 jobs, 486 (67%) were coded as ‘strongly feminine’ or ‘feminine’. 173 (24%) were ‘neutral’, meaning they didn’t contain gendered wording. Only 69 jobs (9%) were coded on the masculine side.

31.7% of the overall jobs posted were from recruitment agencies. Though their stats are better, as evidenced by publishing recruitment agencies such as Inspired Selection making a concerted effort for gender equality, especially at leadership levels, 43% of these jobs coded feminine while only 19% coded masculine.

Generally speaking, jobs coded female sometimes included calls for applicants to be “cheerleader” for the brand, to have a “can-do” attitude, that come with a “personable and warm approach”; while masculine coded jobs sometimes required candidates to be “dynamic” and have a “sense of adventure”.

This is probably not surprising to anyone that has worked within or adjacent to the publishing industry. The industry in the UK is 66% (a level that has been roughly the same in recent years). Therefore a female-driven industry is likely to have female-coded job advertisements, sure.

But if we start to look more closely at the salaries attached to job descriptions, it become apparent that the jobs coded female and strongly female are, on average, lower paid than those coded masculine or strongly masculine. To get this number, I took an average of the high and low salary band; for example, a job with a salary between £45,000 and £50,000 became £47,500.

While not all jobs have salaries in the job description (and very few recruiter jobs provided salary scales), in the 259 jobs that did post salaries, there was nearly an £8,000 gap between the average salary of those coded ‘strongly feminine’ and ‘strongly masculine’.

Strongly masculine reading jobs earned an average of £42,556, and the salary averages descended neatly as the jobs became more feminine coded: masculine: £41,220; neutral: £38,354; and feminine: £34,600, levelling out with those coded strongly feminine.

Most jobs in the publishing industry are coded feminine and are paid, on average, less that the fewer, masculine coded ones.

numbers all in £

It’s not all doom and gloom for those looking for work in the industry. There are positive changes being made in closing the gender pay gap across the industry. Penguin Random House UK saw it’s gender pay gap drop to 0.8% in 2024, and Hachette was named a top 50 employer for gender equality for the UK.

But to address the issues of the gender pay gap head-on, the wider industry has a long list of areas for improvement. These include:

- ensuring that job descriptions are gender neutral to attract a more diverse and stronger pool of talent,

- committing to greater transparency on salaries and the potential for progression, and

- undertaking meaningful, regular and actionable pay audits and equity reviews.

Without committing to these elements, the industry will be unable to achieve the 10 commitments of the Publishers Associations Inclusivity Action Plan, and turnover and will remain high. For a sector struggling with burnout, this is fundamental to bringing things into the current era and continuing to attract and retain high quality, diverse talent to the field.

As an extra bit of info, I also pulled out the publisher that was hiring from each of the 728 jobs. The different imprints at Bloomsbury hired loads of people in the 10 months (+/- 65) and of those 1 was masculine coded, 5 were neutral and the rest were feminine or (most) strongly feminine. Cambridge Uni Press – strongly feminine and neutral. Chatto & Windus – feminine/strongly feminine. DK – 92% feminine. Faber & Faber had a good, even mix of feminine, masculine and neutral. Flying Eye Books – mostly neutral. Hachette and HarperCollins across the board – feminine. Manchester Uni Press – neutral. Michael Joseph – feminine. Nosy Crow – feminine. Pan Mac – 50/50 feminine/neutral. PRH and Quarto – feminine. S&S 13% neutral, 87% feminine. The Stage Media (The Bookseller), 7% masculine, 23% neutral. Unbound – feminine. Walker Books – 100% feminine; What On Earth Books – 100% feminine.

This is a snapshot of the publisher breakdown in their use of gendered language in their job adverts. As mentioned above, recruitment agencies are doing the best in the neutrality of their posts.